|

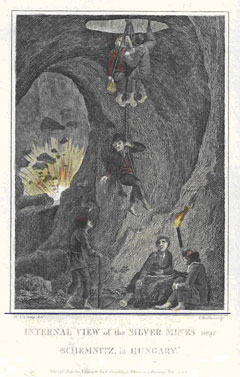

‘Internal

View of the Silver Mines

near Schemnitz in Hungary’

Engraved

by T. Wallis

after

a picture

by

W. M. Craig from

A

Complete and Universal Dictionary

(Bright

& Kennersley) 1812

©

Image courtesy of Ancestryimages.com

|

The

following account appeared in Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal

No. 469 Saturday 23rd Jan 1841, pp 5-6.

Miss Pardoe, in the course of her interesting tour in Hungary, which

has already been noted in these pages, visited the celebrated silver

mine of Bacherstollen, at Schemnitz, of which she gives the following

vivid account. She was accompanied by M. de Syaiezer, the supreme

count of the mines of the district:-

Our

first object was, of course, a descent into the subterranean wonders

of which M. de Syaiezer was the guardian; and the entrance nearest

to the city being by the mouth of the extensive mine called Bacherstollen,

it was at once decided that we should visit on the morrow; and,

meanwhile, we learned that there existed a communication throughout

the whole chain, extending for nearly fifty English miles; the mines

of Bacherstollen alone occupying a surface of about one thousand

square fathoms; its depth being two hundred and the average number

of miners from three hundred and fifty to four hundred.

By

six o’clock the following morning we were all astir; and armed

with a change of clothes for me, we sallied forth to the accountant’s

office, where we were to be furnished with miners dresses for the

gentlemen, and our guides with lamps for our underground journey.

There we were joined by a young Milanese count, a student at the

university; and although three handsomer men will rarely be seen

together than the companions of my intended expedition, yet when

they came forth in their leathern aprons, black caps and coarse

jackets with padded sleeves, all encrusted with yellow clay, I began

to fancy that I must have suddenly fallen among banditti; nor was

the conceit diminished when the miners, who were to accompany us,

joined the party, with their smoking lamps in their hands, and (if

possible) ten times wilder and filthier looking than the gentlemen.

Away

we went however, and ere we had taken a hundred steps we were in

utter darkness. A low door had been passed, a narrow gallery had

been traversed, a few stairs had been descended, and we were as

thoroughly cut off from the rest of the world, as far as our outward

perceptions were concerned, as though we had never held fellowship

with them. We were moving along a passage, not blasted, but hewn

in the rock, dripping with moisture, and occasionally so low as

to compel us to bend our heads in order to pass; while beneath our

feet rushed along a stream of water which had overflowed the channel

prepared for it, and flooded the solitary plank upon which we walked.

But

this circumstance, although producing discomfort for the first few

moments, was of little ultimate consequence, for the large drops

which exuded from the roof and sides of the gallery, and continually

fell upon us as we passed, soon placed us beyond the reach of annoyance

from wet feet, by reducing us to one mass of moisture.

So

far all had been easy; we had only to move on in Indian file, every

alternate person carrying a lamp, to avoid striking our heads on

the protruding masses of rock, and endeavour not to slide off the

plank into the channel beneath, and thus make ourselves more wet

and dirty than we were. But this comparative luxury was to soon

end, for ere long we arrived at the ladders which conduct from one

hemisphere to another, and by which the miners ascend or descend

to their work. Then began the real labour of our undertaking. Each

ladder was based on a small platform, where a square hole sawn away

in the planks made an outlet to arrive at the next; and as these

had been constructed solely for the use of the workmen, it was by

no means easy to secure a firm footing upon all of them, particularly

as the water was trickling down in every direction, and our hands

stuck to the rails which were covered in soil.

When

we arrived, heated and panting, at the bottom of the first hemisphere,

the chief miner led the way through an exhausted gallery, whence

the ore had been long since removed, and which yawned dark, and

cold and silent, like the entrance to the world of graves. The half-dozen

lamps which were raised to show us the opening, barley sufficed

to light the chasm for fifty feet. The distance defied their feeble

power; but the jagged and fantastic outline of the walls, partly

blasted, and partly hewn away where the practised hammers of the

workman had followed up a vein of ore, to my excited fancy to take

strange and living shapes as the heavy smoke of the lamps curled

over them – bats and serpents clung to the ceiling –

phantoms of men and beasts supported walls – and in the midst

moved along a train of wizard beings, neither men nor demons.

To

the right of this gallery opened another vast cavern, cumbered with

large masses of rock, but of which we could see the whole extent.

This was what is technically called in the mines a ‘false

blast’, where, after having made an opening, the miners ascertained

that the ore had taken another direction, and that this was mere

rock, which it was useless to work further. Hence we passed through

another gallery similar to the first, except that it had been produced

by blasting, and that the various nature of the rock had rendered

it necessary to line it in many spots with stout timber.

There

are five distinct methods of doing this; and they are applied according

to the degree of strength required to resist the superincumbent

and surrounding mass; sometimes the planks are placed perpendicularly,

and roofed over with flat boards, like a hovel; at others the formation

of the gallery resembles a low Gothic crypt. In many instances the

timber is arranged transversely - in others horizontally; and, finally,

there are particular places where blocks are driven into the solid

rock like piles of a bridge, and support a perfect erection, shutting

out every glimpse of the rock itself.

The

sight of these precautions gave me an uncomfortable feeling, for

their very necessity implied a certain degree of danger; and although

cowardice is not my besetting sin, I confess that I should not like

to occupy quite so capacious a grave as the mine of Bacherstollen.

Another

set of ladders, as steep and sticky as the last, admitted us into

the second hemisphere; and on reaching it we came almost immediately

upon a gallery in which the ore had been followed up until the vein

had become exhausted. In order to enter it, we clambered over the

large masses of stone which had been severed from the rock by blasting;

and when we were fairly gathered together in this gloomy cavern,

for such it was, and when our guides raised their lamps, and moved

them rapidly along the roof and sides of the chasm, it was beautiful

to see the bright particles of silver flash back the light, and

to follow the sinuous course of the precious metal, which was so

clearly defined by those glittering fragments.

Many

large lumps were also strewn beneath our feet, which appeared to

pave the earth with stars, but they had not been considered sufficiently

full of ore to render them worthy of being transported to the surface.

These exhausted galleries are gradually refilled with soil and stone

in the process of mining, as the rubbish removed in each new excavation

is flung into them, by no means a disagreeable reflection, I should

imagine, to the inhabitants of Shemnitz, whose dwellings stand immediately

above a portion of Bacherstollen.

It

was curious enough, when on one occasion we came upon an immense

iron pipe cutting through the side of the gallery along which we

were passing to see M. de Csapoj stop before it, and announce that

it was that of the town pump, in the centre of the square which

we had traversed in the morning; and that a little farther on, we

were standing under the house the supreme count, with whom, on our

return to the surface of the earth, we were to dine.

Shortly

after passing this pint, I perceived that a very earnest discussion

was taking place among my conductors, nor was I long in discovering,

from the frequent hesitating glances which the chief miner turned

upon me, that I was its subject. As a matter of course, under these

circumstance, I begged to be made a party in the consultation, when

I ascertained that some doubt had arisen whether I could be permitted

to descend lower, as I had now arrived at as great a depth as any

lady had yet attempted; but I had no inclination to stop short so

soon in my undertaking, and when I found out that I was the first

English woman who had ever entered the Bacherstollen, I pleaded

my privilege accordingly; but it seemed that they feared the displeasure

of M. de Syaiezer, as the miners below were employed in blasting

rock in every direction.

As

it was, however, quite impossible that I should consent to leave

the mine without witnessing this, the grandest exhibition that it

could offer, I only insisted the more strongly on the assurance

which I had received from himself, that everything should be done

that I desired; and satisfied, when rid of the responsibility, the

miner once more led the way to the ladders, and we commenced our

third descent – the only variation being produced by an intense

feeling of heat, increasing as we got lower, and a suffocating smell

of sulphur, the natural effects of the work which was going on,

two hundred explosions having already taken place since sunrise.

This result of the blasting, as regarded the ore, had not yet been

fully ascertained, but there was every reason to believe that it

had been very satisfactory.

When

we arrived at the bottom, the sensation was all but suffocating;

the dense vapours seemed to fold themselves about our wet garments,

and in a few seconds we were enveloped in a steam which produced

intense perspiration, and a faint sickness that compelled us to

disburden ourselves of all the wraps by which we had sought protection

against the damps above.

For

a time we all stood still, quite unable to penetrate farther; and

even those of the party who were accustomed to encounter the confined

air of the galleries, were glad of a moment’s rest; for the

explosions had followed each other with such rapidity, that the

atmosphere had as yet had no time to relieve itself of the sulphurous

vapour with which it was burdened, and which created an exudation

from the rock, that brought water down upon us in tepid drops in

all directions.

We

spent upwards of an hour strolling through this section of the mine,

in order to give time to the workmen for completing a bore on which

they were labouring, to enable me to witness a blast – our

conductor obligingly putting more hands to the work to expedite

its completion; and during this hour we only encountered three miners,

although nearly three hundred were at the moment employed in that

particular hemisphere – a fact that will give you a better

idea of this subterranean wilderness than any attempt to describe

its extent.

There

was something almost infernal in the picture which presented itself,

when we at length returned to the spot where the next blast was

to take place. A vast chasm of rock was terminated by a wooden platform,

on which stood the workmen, armed with heavy iron crowbars, whose

every blow against the living stone gave back a sound like thunder.

One small lamp, suspended by a hook to a projecting fragment, served

to light them to their labour; and it was painful to see how their

bare and sinewy arms wield the ponderous instrument, which at each

strike sent a quiver through their whole frame. I ascended this

platform, which was raised about six feet from the rock-cumbered

floor of the gallery, in order to see the process of stopping the

bore, and thence I had a full view of the frightful scene presented

by the vault.

At

length the bore was completed, and a small canvass bag of gunpowder

was inserted into the hollow, nothing remaining to be done but to

add the fire by which it was to be exploded. This is applied in

a substance which it requires some seconds to penetrate, in order

to give the workmen some time to retreat to a place of safety. We,

of course, declined to remain for this latter ceremony; and made

our way, before the insertion of the inflammable matter, to the

spot which had already been decided on as that whence we might safely

await the explosion – a large opening, situated behind an

abrupt projection, where an exhausted gallery terminated, and where

no mass of rock could reach us in its fall – and we had scarcely

crowded together in our retreat, ere we were followed by the workmen

at the top of their speed, who, after having secured the aperture

which it had cost them so many hours of labour to effect, had rushed

to the same spot for safety form the effects of their own toil.

There

we remained for full three minutes in silence, listening to the

quick panting of these our new associates, ere the mighty rock,

riven asunder by the agency and cupidity of man, yielded to a power

against which, after centuries of existence, it yet lacked the power

to contend, and with gigantic throes gave up the hidden treasures

it had so long concealed. Surely there can be no convulsion of nature

produced by artificial means, so terrible and overwhelming in its

effects as the blasting of a mine. First comes an explosion, as

though the artillery of an army burst upon the ear at once, and

the vast subterranean gives back an echo like the thunders of a

crumbling world; while amid the din there is a crash of the mighty

rocks which are torn asunder, and fall in headlong ruin on every

side – each as it descends, awaking its own echo, and adding

to the uproar; then, as they settle in wild ruin, massed in fantastic

shapes, and seeming almost to bar the passage which they fill, the

wild shrill cry of the miners rises above them, and you learn that

the work of destruction is accomplished, and that the human thirst

of gain has survived the shock, and exults in the ruin that it has

caused.

So

strange and exciting an effect does this phenomenon produce, that

I actually found myself shouting in concert with the poverty-stricken

men about me, governed by my nerves rather than my reason, and with

as little cause for exultation as themselves. To me it was nothing

that another portion of the earth has been torn asunder, thews and

sinews, and scattered abroad in fragments; it could not operate

upon my individual fortunes; and the shirtless wretches about me,

who had raise a wild clamour, that would have seemed to indicate

that they rejoiced over a benefit obtained, like myself had only

obeyed their excited senses; for they were poor, and overtoiled,

and shirtless as ever, even thought the rock which they had just

riven should have opened a mine of wealth!

I

need not explain that this last explosion had by no means improved

the nature of the atmosphere, and we were accordingly not slow in

preparing to depart. But my entreaties to descend yet lower proved

abortive; not an individual of the party would listen to me; and

I found myself compelled to obey, from sheer incapacity to persist;

and I knew, moreover, that I must husband my powers of persuasion

in order to induce my companions to permit me to ascend by the chain,

an operation so formidable that it had never yet been contemplated

by one of my own sex.

To

me, the ascent by tiers of six and thirty ladders appeared infinitely

more distressing than any process where violent exertion was rendered

unnecessary by machinery; and I consequently felt no inclination

to retreat when I was requested to look up and down the shaft, near

the centre of which I stood, and to examine the chain by which I

was to be drawn up, and the leathern strap upon which I was to be

seated.

There

could be no positive danger where both were solid; and it was perfectly

clear, that if barrels of ore could be drawn up by the same means,

my weight and that of the miner who was to ascend with me, must

be very inconsiderable in comparison. I therefore only requested

that the apparatus might be got ready; and amid the wondering murmur

of the men who steadied the chain, took my seat upon the sling,

and having been raised about six feet above the mouth of the trap,

hung suspended until my companion followed my example.

We

then commenced our ascent; and although the sensation was very peculiar,

it did not strike me that it was one calculated to create terror.

All was dark above, and, save the lamp attached to the arm of my

companion, all was dark below; consequently there was nothing in

the aspect of the shaft to shake the nerves. The only inconvenience

arose from the occasional twisting of the chain, which from its

great length (nearly six hundred feet), occasionally swung us suddenly

round, and then righted itself with a jerk, when we had to guard

our knees from contact with the timbers which lined the side of

the pit; but save this temporary drawback, the motion was rather

agreeable, and wet and weary as I was, I should have preferred ascending

thus half a dozen times, to braving the fatigue of the ladders.

It

is impossible to imagine what scarecrows we were when the light

of day once more shone upon us, now how oppressive the heat of the

sun appeared when we emerged from the mouth of the mine: as for

me, I could scarcely move under the weight of my clinging garments,

and did not recover form my exhaustion until I had plunged in a

tepid bath; by whose beneficial effects I was, after an hour’s

repose, enabled to prepare for M. Svaiczer’s dinner.

I

wish that I could do justice to the courteous urbanity and kindness

of this talented gentleman; but feeling how inadequate any praise

of mine must prove in such a case, I can only declare, that among

my most pleasant and enduring memories will be the obligations which

I am under to him, both as a traveller and a stranger.

|